user research findings and insights

what we did

We’ve been working in the whenua Māori and geospatial data space for a while now. We saw a gap between the information Māori land owners and whānau need to know about their whenua regarding agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and the information that’s available to them currently. We think people can be empowered and supported to make informed decisions about their whenua if they have useful and useable data and information.

We came up with the idea of creating a digital tool to provide Māori land owners with resources about whenua and GHG emissions, and we’re developing this in partnership with Toihau – the Māori Advisory Board at the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC).

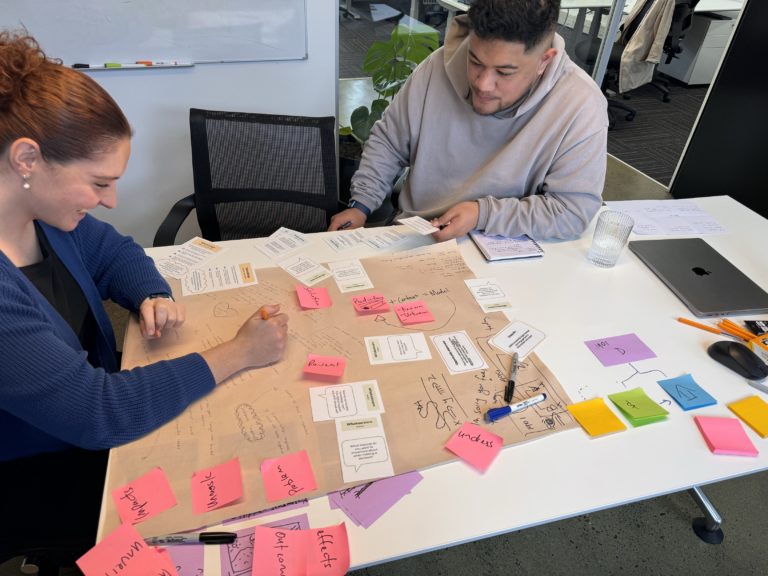

We completed 2 phases of user research, starting broad to understand the beliefs, drivers, aspirations, and challenges related to agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and whenua. We wanted to test the hypothesis that if we make data and information accessible and understandable, then people will be more likely to care about climate change and act to reduce their emissions.

We talked to Māori land owners and their whānau and learned that this was not true. Access to understandable information was not enough to make people care, and there were other things that they valued and cared about first. These findings shifted the focus of the second phase of user research to reframing and rebalancing the confusing, disengaging, and disempowering narratives surrounding agricultural greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), farming, and whenua Māori.

We’ve shared the findings and insights from our user research below. While it was focused on a particular problem, you may be able to build on these findings and insights in your own work.

Phase 1

We travelled around the motu, from our neighbourhood in Wellington, all the way to Hauraki, holding interviews and workshops with Māori land owners and organisations whose kaimahi are involved with Māori engagement or climate change. People could see the gap we were addressing with the project and were happy to share their thoughts and experiences. Here’s what we learned:

People don't really care about agricultural greenhouse gas emissions

The effects of GHG are hard to connect to and using this terminology does not help. We heard that people care about their feeling of connection to their whānau, awa, whenua, and taiao. Looking after many of these elements can lead to the reduction of emissions, even if that was not intended. For example, using less fertiliser near waterways to protect the health of the awa.

Conversations or messaging should be framed around what is important to people and what they can connect to, so they can make the link to climate change impacts and choose to care or take action. This would be more effective than being told to care or reduce emissions with legal obligations.

Even if people cared they would find it hard to act because it is complex and overwhelming

The systems that people need to navigate to understand agricultural greenhouse gas emissions are confusing, complicated, unresponsive, and Western. This includes legislation and regulations which impact people, but they had not been involved in designing or consulted on. Even if they manage to navigate the systems, it can be hard to know what to do with the information and what actions are possible.

There is a lot of existing Information, but it may be in systems that require licences to access or written in a way that is hard to use. Scientific research and data is valuable, but they need to be in a format that people understand so that it can applied to the real world.

People have different ideas about what data and information is – for many people the whenua itself is data

How people think about data and information is different from how data providers like the Crown, scientists, and consultancies think about it. There are signs that people interpret from the whenua and what’s happening on it (like the eel running) through a lens of their own mātauranga.

These are trusted data points collected over generations, used to make decisions and often not captured in research. Their value should be recognised. Information from data providers can be used to support and increase understanding of why whenua is the way it is.

Access to the right data and information is often based on relationships

People who already have established relationships and contacts with Crown agencies and partners find it easier to access the right data and information for funding or to help with making decisions about the whenua.

Not everyone is at the same starting point when access is based on knowing the right people. It is another challenge when there should be a standard level of data and information that is available to everyone.

The people who already do care about agricultural greenhouse gas emissions have a deep connection to the whenua

People describe their contribution to the whenua as a kaitiaki in many different ways. People who already care about GHG emissions have a deep connection and relationship with their whenua, the taiao, their whānau and hapū. Through their unique journey of connecting to their whenua and whakapapa, they have identified this issue as important to their whenua and in their context.

People who are less connected to their whenua and whānau tend to care less about emissions.

Whānau needs are the immediate focus

“We don’t care about greenhouse gas emissions! We care about our whenua, our awa, our moana, our whānau, therefore we care about greenhouse gas emissions.”People have immediate issues that they are grappling with daily (e.g. paying for food and bills) and don’t have bandwidth to address other issues. Climate change and reducing GHG is not front of mind. There is blame, shame, and guilt associated with this, but also a disconnect between what is pressing and what they are told to care about.

Land use choice – change without choice is a demand

“People are hōhā with regulations and Crown’s carrot and stick approach to change, particularly around whenua use.”People want choice – to decide whether to change their land use or not. They want to make their own decisions (even mistakes) in their own time and in their own way, accountable to themselves and their whānau.

They need the options without the threat, because prescribing a solution without understanding people’s context is disrespecting the mana they hold with their connection to their whenua and uri. People are so used to this happening that they expect it. This can be seen through the approaches and regulations of various agencies and organisations.

MY journey of hōnonga is linked to OUR journey to oranga

“People [decision makers and Crown] need to recognise the other contributing factors leading to connection and disconnection between whenua.”Each journey of connection to whenua is unique because the reconnection to whenua and whānau is an individual and personal process. It isn’t a continuous or linear path, but each journey leads to connection. People have trauma to deal with, barriers to overcome and priorities to shift that are interconnected to their disconnection away from whenua and hapū.

There is a disconnect within systems and procedures and the recognition and importance of the connection of the individual and their hapū. Nāku te rourou, nāu te rourou, ka ora ai te iwi.

People can’t act without removing the shackles of the many whenua systems and rules

“People don’t need any more regulations or ‘paperwork’ or costs. They hinder our advancement of whānau.”Navigating legislation, regulations and norms constrains Māori action at every part of the process. Accessing data, making decisions, reporting, even simply connecting to your own whenua is held back by systems and rules.

There is a perceived lack of acknowledgement by the Crown on how their actions impact whenua Māori and whānau because they continue to happen, and there are many examples of Māori having to fix problems that were imposed on them by the Crown.

Access to information doesn’t make an issue matter

“Trust and respect helps people to access information, they need to care about the information to engage with it.”People need to care about something before they can turn information into action. They also need to deeply care about something before they will deviate from what they are familiar with.

People are overwhelmed by daily tasks and have limited bandwidth to engage with new issues. Providing access to information doesn’t guarantee engagement or action. People need to care about the topic first before taking action.

Māori do not have power and control over their whenua or their farms

“People want to control the trajectory of their future, whether that be in their home life or their work life.”People feel so far from having power and control over their whenua or their farms. They are price takers, they are left out of Crown-led processes, they are forced to meet or operate in certain ways by legislation, or their trusts have different aspirations.

People feel this way in many other systems that they encounter in their daily life. They want autonomy over themselves and their hapū, and support to self-determine where they are going and how they will get there.

Phase 2

To address the findings from Phase 1, we shifted our user research focus away from data and information to reframing and rebalancing the confusing, disengaging, and disempowering narratives surrounding agricultural GHG emissions, farming, and whenua Māori.

We explored the opportunities of:

- how can we create pathways that bridge and connect people back to their whenua, whānau, and te taiao?

- how can we define, recognise, and elevate the attributes and skills to realise kaitiakitanga within people?

And understanding:

- how our audiences are active and participating in this space

- the harmonies and tensions our audiences experience with digital resources and data providers

- the forms that kaitiakitanga takes within our audiences.

We learned that there is a common user journey across many different profiles.

People’s journeys, actions, and goals were similar in structure. There is a core set of actions that people take at various points in their journey. The emphasis of actions is different for people at different times in their lives, and there are many paths between the actions.

Connecting

- Involves a deep sense of community, shared identity, and respect

- Connecting to the land and ancestors

- Celebrates the importance of relationships among people, and people and the natural world

- Unique and rewarding journey addressing a range of barriers

Learning

- Acquiring new knowledge and skills through various experiences, interactions, and resources

- Continuous and evolving – involves active engagement, reflection, practice, and openness to new perspectives

- Expanding understanding and the desire to discover and grow

Deciding

- Making a choice or reaching a conclusion after considering options, factors, and outcomes

- Balances rational and emotional thought processes, weighing up pros and cons, and assessing risks

- Impacted by the context in which the decision is being made for

Supporting

- Depends on the needs of the person or situation

- Recognising what they need most at a given time

Doing

- Taking action that leads to change or delivery, moving from planning or intending to do something

- Can involve many different small steps

- Depends on context, people’s objectives and roles

Influencing

- Ability to affect the thoughts, behaviours, and decisions of others

- Can involve persuasion, communication, leadership, and relationship building

- Inspiring change, gaining trust and buy-in from individuals or groups, collaborating towards shared goals

- Adapting approaches to the situation and audience for positive and meaningful change

We need to recognise the importance of the journey, not the destination

“It’s not a finite verb, there’s always learning and development to be done, you’ll never be a perfect kaitiaki because there’s always more to learn”People could describe what being a kaitiaki looked like and how they could see it in others, but were hesitant to recognise that they were one. They could appreciate and describe their kaitiakitanga journey and where they were in it, but it was like an unattainable ‘status’.

Māori need to feel empowered to feel that any sense of being kaitiaki that they recognise within themselves, is worthy and of value to their whenua. Definitions and examples of kaitiakitanga vary and often emphasise celebrating those making big decisions and contributions to their whenua. This results in a certain status being required to ‘become’ kaitiaki, instead of recognising all the pieces of the puzzle.

Digital can never replace physical experiences that nurture connection

“Recognising kaitiaki, for myself and my role in my whanau, I feel like I am kaitiaki for connecting with my whanau, for connecting with them and my whenua and whakapapa.”Kaitiakitanga is a philosophy that people described demonstrating in different ways. All the examples we heard included deepening their connection to the whenua, to connecting with whānau and sharing knowledge. Some examples described digital tools as helping enable further connection, such as using Zoom for meetings and whānau accessing information to make decisions.

Whānau Māori have always connected to their whenua in a physical and spiritual sense, and digital solutions cannot replicate or act as a replacement in strengthening connections or helping someone recognise themselves as kaitiaki. It can, however, enhance connections by acting as a bridge.

Dictating a ‘focus’ limits possibilities and stifles uniqueness

“We don’t over farm the land. Our land is under the carrying quantity, and we keep it how it’s been. If we had more grass than a year before, well, then we have extra that year. We don’t then aim to have that same amount the next year or to beat it.”Whānau use various values and principles when making decisions about the whenua, giving them different weightings depending on context and the priorities for their whenua and whānau. This comes from a deep understanding of the land from caring and nurturing it over centuries. Typically, profitability or economic success were weighted lower, unless it helped strengthen or elevate a core value. For example, giving rangatahi financial assistance at university.

When whānau are not being confined to prioritise profitability, growth, or other Western expectations, we saw them gain confidence and freedom, and use their creativity to grow and enhance the activities on their whenua.

Suggestions or guidance without listening first is a form of direction. And dictating a focus or priority limits Māori and their opportunities and stifles the uniqueness of their relationship with their whenua and te taiao.

Our digital tool needs to recognise and respect all the values and principles that Māori consider when making decisions about their whenua to empower the autonomy. It must first listen, then respond.

The colonised system alienates Māori from their whenua

“If you’re Māori, you come from somewhere. It doesn’t matter how weak or strong the connection is. You don’t even have to know about the whenua to be connected, it’s in your blood. One day you then might know about it and your connection will be strengthened.”There are roles (with perceived capabilities) that carry a weighting and value acknowledged by systems and processes that whānau need to interact with. For example, a land owner today or in the future. Those systems have been adopted through force and bled across our culture and our whenua, and fails to recognise everyone’s value or contribution. That lack of recognition leads to disconnection and alienation.

The system implies there’s only one pathway to be taken, and when you’re on this pathway you do certain things as you move along the pathway. However, there are multiple pathways into connecting and participating with your whenua. The value is not as simple as ‘being on a trust’ or ‘being a landowner’. Connection and participation have various forms and is not measured in a certain way.

Celebrating all forms of value and contribution that whānau bring and create for their whenua needs to be a priority. Nurturing all forms of connection already established is important in strengthening the whenua and fostering deeper and stronger connections. We need to stop isolating those whose connection or value is deemed as not strong enough by our systems and awhi them to a space of mana.

Empathy across generations preserves the knowledge that’s important in caring for the whenua

“What I've learnt and has been my best tool for learning in the last decade has been korero through my mentoring work with the younger generation.”Māori believe they don’t inherit the earth from their ancestors, but borrow it from their mokopuna, and this speaks to the weight that today’s decisions carry. There is an element of blame culture in the current narratives associated with whenua/enterprise and fundamentally climate change impacts. There is also a lack of acknowledgement of the tools and resources available to our land owners and decision makers or the context they sat in while making decisions years ago. We know more today than we did in the past and we have different priorities and focuses than we did 10 – 100 years ago.

Mātauranga Māori is shared through knowledge being passed down through generations, and reframing the narrative to observe empathy rather than blame helps to strengthen intergenerational relationships and preserve the knowledge that’s important in caring for the whenua.

user goals for the digital solution

We heard throughout our research there were goals that people wanted to achieve by using the digital solution. These user goals need to be met for the solution to be successful and sustainable. They are:

- To break the barriers that are stopping me from connecting with my whenua and whānau

- To connect with my whenua and whānau

- To explore possibilities for reducing agricultural greenhouse gas emissions from activities on my whenua

- To plan and act

- To understand and reflect on the impacts of decisions on my whenua, whānau, and te taiao.

As part of our website strategy, we mapped user profiles, what actions they take and need support with during their user journey, and what they want from the digital solution. This helps us design the solution with their context and needs in mind.

We also explore user goals and needs, the unique value proposition for He kai kei aku ringa, and some initial concepts to realise this and the opportunities.

Back to Our Projects